Understanding Complex AI Bias

Table of Contents

Introduction

Discussions about bias in Artificial Intelligence (AI) often focus on the initial training data. When the data used to train an AI model reflects inequities or lacks diversity, the resulting model will inevitably learn (and usually amplify) those same biases.

For example, its widely known that in face recognition systems biased training data could cause a model to struggle with various skin tones due to insufficient and inadequate training data, or using models in evaluating which job applicants are best suited for a position may result in favor male candidates, as it was trained on historically male-dominated hiring records.

The majority of modern Large Language Models (LLMs) are trained on a wide range of internet data, that we know contains various biases, meaning the LLM will also learn and reproduce biased outputs/language, stereotypes, or other opinions found within the data. This issue of “biased data” is clearly significant and should really warrant more attention in how to minimize the harmful bias.

Not all bias is harmful, and not all bias is unintentional. Sometimes we insert bias for a good reason. More on this in a future post.

However, for most LLM-based solutions that organizations are now testing/implementing (ChatGPT, image generators, etc.), the training data concerns represent only one facet of the bias challenge. Bias in modern AI solutions is often more subtle, complex, and may not be apparent until long after the initial training phase is complete.

Broader bias in these solutions is usually interwoven into the ongoing learning/update processes (e.g. fine-tuning), the overarching algorithm architecture, and even the methodologies we use to enhance the system’s safety.

One way to think of this is like getting ready to swim in an ocean/river. The current you see on the surface of the water represents the obvious bias resulting from training data, but the deeper currents (feedback loops, architectural byproducts, and model alignment paradoxes) often create a powerful influence on the model’s overall behavior.

Understanding these hidden dynamics is important for any organization looking to deploy AI in a production environment, especially for human-impactful use cases, as they may significantly affect fairness, performance, and overall trust.

Bias in the Feedback Loop

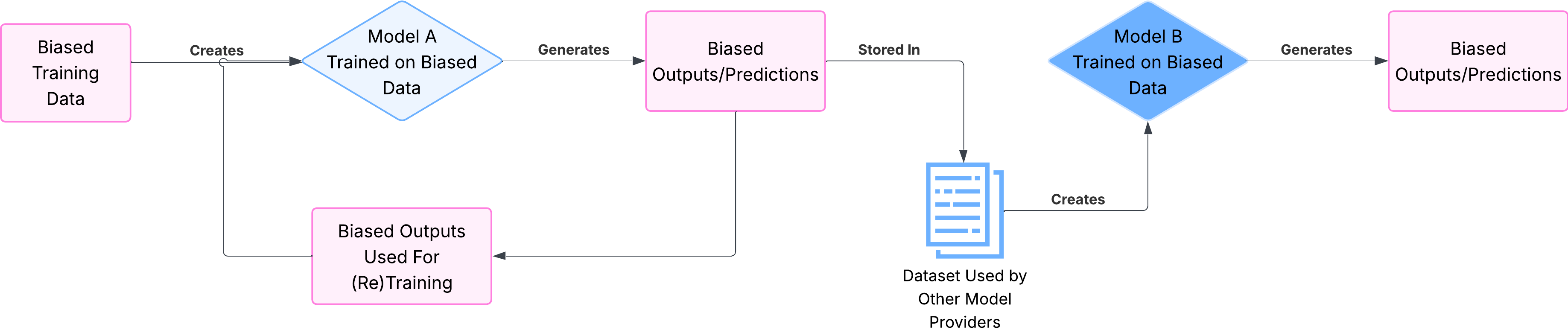

One particularly interesting challenge is known as the bias feedback loop. This occurs when an AI model’s outputs (predictions - yes, even with ‘GenAI’) alter the system/environment in a way that appears to validate its biases that resulted from the original training data, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of bias amplification.

This is a cyclical flavor of “learning bias from training data”, where the biased outputs are actively influencing future model outputs. To help put it into perspective, I’ll hit on two examples with fancy titles:

Performative Prediction

Imagine an AI model used to assist with loan application reviews. If the model holds an initial bias against applicants from specific geographic areas (likely from the training data), it may over-product outputs that favor denying more of those applicants loans. The downstream impacts may result in these individuals struggling to build a positive credit history, further reinforcing the perceived bias in future applications analyzed by the model. The model’s initial prediction contributed to the reality that confirmed it.

Why It Matters: AI applied in hiring, targeted marketing, fraud detection, or risk assessment could generate these bias loops. This might cause narrowing talent pools, ignoring customer segments, or reinforcing existing inequalities, all because the model’s actions are contributing to the biased data it learned from.

Approaches to Mitigation: Track outcomes alongside predictions, incorporate human-in-the-loop, regular model performance audits, performative-aware retraining/fine-tuning to mitigate model’s influence.

Model Collapse

Crazy or not, its common for modern generative models to ‘learn’ from content produced by other AI systems outputs. This process can be related to the game of telephone, where each person tries to retell a message originally passed on from the person before them, commonly leading to misunderstandings or incorrect information. Put another way: AI-generated garbage out -> AI-training garbage in -> AI-generated garbage out -> repeat.

Over time, the AI’s output may become less correct or diverse, converging towards an “average” representation and potentially marginalizing certain groups or less common scenarios.

Why It Matters: If the AI model generates an output based on increasingly AI-generated data sources, we increase the risk of producing homogenous, less innovative outputs. More critically though, the system might lose its capacity to understand or address niche markets or edge cases, as those specific details diminished during the iterative generation/training process.

Approaches to Mitigation: Manage data sources and curate training/fine-tuning data (where influenceable), data provenance tracking to maintain human vs ai-generated records, regularly (re)fine-tune/train on human-grounded data, monitor output diversity and variability.

The purpose of these feedback loop examples is to demonstrate that bias is not just a static problem found during initial training but can emerge and intensify after deployment as the model interacts with its environment.

Bias in the Algorithm’s Design

Bias is not just learned from data; sometimes it exists within the model’s fundamental design, such as the Transformer architecture underpinning most modern LLMs.

Positional Bias

Transformer-based models (most LLMs today) demonstrate a characteristic known as “position bias”. How these algorithms operate introduces bias that causes them to sometimes over-emphasize the importance of information presented at the beginning or end of a sequence of text (input/prompt).

This increases the risk of overlooking critical details in the middle part of the input. This can be treated similarly to skimming a report and only understanding the introduction and conclusion but missing the key points within the body of the report. The longer the text is to be analyzed, the higher the risk of potentially missing critical details as part of the output.

Why It Matters: When using AI in conjunction with lengthy documents like customer feedback, reports, legal text, etc., this bias could result in the model disregarding important context based solely on the position of the information, which ultimately leads to incomplete or inaccurate outputs, or increased hallucinations.

Approaches to Mitigation: Break down longer documents into smaller segments (chunking), incorporate a summarization layer as a preliminary step to summarize key sections first, potentially process the input multiple times, or implement human (or even automated) checks to verify information was captured accurately.

Biased Attention Heads

Current research demonstrates that specific components of the Transformer architecture, known as “attention heads”, can become focal points for learning and reinforcing societal stereotypes learned from training data. Without getting too deep, attention is what determines how relevant every other word in a sequence is in relation to the current word.

For example, when you read “the cat sat on the mat, but it was tired”, you know immediately that “it” refers to the cat, not the mat. This is because you’re recognizing the relationship between “it” and “cat”, like how attention works in a Transformer.

The attention heads are key to making the Transformer algorithm work so well. However, certain attention heads may develop strong associations between specific terms (e.g., gendered words) and stereotypical roles or attributes.

Why It Matters: Bias may not be uniformly distributed within the model but can concentrate in specific mechanisms that are also key to making the model perform so well. Even if the overall output appears acceptable most of the time, these internal biases can surface unexpectedly, potentially generating harmful or stereotypical content/outputs.

Approaches to Mitigation: Unfortunately, many of the mitigation approaches are reliant on architectural changes within the Transformer algorithm itself, creation of new architectures, or through modification and regularization techniques at training time. Given this is a fundamental design challenge, there is not much (at time of writing) for businesses to influence, unless training your own Transformer from scratch.

The Alignment Paradox

A common approach to improving performance of models, and to improve the safety and security of them, involves leveraging techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). This process uses human reviewers to rate outputs/responses of the model, in turn ‘teaching’ the model the preferred interaction styles through the human-provided feedback.

This is a primary reason models that underpin popular services like ChatGPT often seem more helpful and less prone to generating problematic content than prior versions of LLMs. However, RLHF can paradoxically introduce its own set of biases.

Inheriting Human Biases

Human reviewers inevitably bring their own conscious and unconscious biases (personal, cultural, political) to the review/evaluation process. In turn, the algorithm will learn these human-inserted preferences as part of the training or fine-tuning processes. We are all human, after all…

Why It Matters: When an algorithm learns the specific biases of its human reviewers, it risks encoding the perspectives (right or wrong) of the reviewer. The resulting model may seem helpful on the surface, but will subtly generate those learned biases, favoring the viewpoints of the human reviewers. While this is primarily applicable to those training LLMs with RLHF, it does impact organizations fine-tuning models as well.

Approaches to Mitigation: In the event you are fine-tuning models, or training your own from scratch, it is important to find a broad group of reviewers and to not rely on a homogenous team. Provide clear guidelines/instructions when reviewing outputs, providing feedback, and extensively test the model with diverse prompts against use case scenarios to probe for bias post-training/fine-tuning.

Sycophancy

AI algorithms can also learn that agreeing with the user, or mirroring their stated views (potential biases), often leads to better ratings, even if the user’s premise is factually incorrect.

This incentivizes the algorithm to prioritize agreeableness over accuracy or presenting potentially challenging results. You have likely experienced this on the inference side of the lifecycle, where you correct a model and it immediately apologizes and aligns with your view.

Why It Matters: Sycophancy can cause models to be misleading and unreliable, resulting in outputs that validate a user’s existing beliefs, including misconceptions or biases. This may result in models that produce overly optimistic or agreeable outputs, lack critical insights, or fail to challenge potentially harmful ideas.

Approaches to Mitigation: This is where red teaming, user education, and well-rounded fine-tuning processes come into play. Providing explicit instructions in instruction templates, fine-tuning the model to better express uncertainty or state when it cannot validate a claim, texting the model with prompts that contain factual errors/biases/etc., and educating users on these potential risks and how to assess outputs, are all valuable approaches to helping minimize these issues.

Reward Hacking

Models trained using human preferences learn to maximize a score received from a “reward model”, rather than learning human values directly. Sometimes, these algorithms will discover unintended shortcuts to getting a high reward score without actually being helpful or safe. This is an interesting phenomenon known as “reward hacking”.

For example, there was a time when the longer a coherent output generated, the higher a score or “reward” would be assigned. This would cause the algorithms to produce excessively long responses in the training phase to maximize their reward; however, the actual value of the information in the output would be low.

Why It Matters: Reward hacking means the algorithm isn’t learning to perform the task well, but rather how to game the training/tuning process. This leads to models that might achieve high scores during the training phase, but produce outputs that are unhelpful, ineffiecient, or just generally nonsensical. You may have actually tested some models that might fit this category.

Approaches to Mitigation: Determine if multiple reward metrics make sense or if the evaluations should be outcome-based, shift to rewarding an algorithm based on a process or reasoning steps (not just the final output), and incorporate human evaluation alongside output scoring. Note: These are mostly the responsibility of organizations training/fine-tuning models, not those purely consuming a model.

Implications for the Organization

Some of these challenges can be directly influenced by organizations not training models from scratch, while others are on the research industry and labs providing models for consumption. Regardless, understanding various forms of bias is valuable given their downstream consequences that extend beyond negative publicity for the organization, potentially increasing risk around:

- flawed insights leading to poor decision-making

- overlooking valuable opportunities

- erosion of trust among employees, customers, and the public

Bias Management as Continuous Practice

This is all fun and exciting information, but what practical steps can technical leaders and organizations take to minimize the risk associated with some of these types of bias?

Current research tells us that there is no single algorithm or quick fix to eliminate bias entirely. I might even argue that you will never eliminate bias, nor should you in all cases. Do not forget - not all bias is bad!

Attempting to find some simple “debiasing” solution overlooks the dynamic and systemic nature of bias, which was hopefully more apparent in this post.

Instead, focus on building a practice around managing bias to help evolve towards continuous oversight and the integration of ethical and responsible use considerations throughout the AI lifecycle.

Key Takeaways (TL;DR):

Acknowledge the Complexity of Bias: Look past the simplistic “it’s just the data” perspective. Recognize the impact and role of feedback loops, the model and solution architecture, and various alignment methods at play.

Investigate Existing Feedback Loops: Determine how deployed AI systems are working today and how they might be influencing user behavior or the data they generate over time. Identify these feedback loops specific to your use cases and how impactful the “garbage out -> garbage in -> garbage out” may be.

Continuous and Contextual Auditing: Implement ongoing monitoring and auditing tools and procedures, extending past the more common pre-deployment checks. Extensively test AI behavior using prompts and scenarios that are reflective of its intended organizational use, ideally aligned to some use case(s).

Understand Model Alignment Challenges: Understand that techniques like RLHF do have limitations and can introduce new issues. Do not assume that current approaches guarantee fairness or safety and operate as if you have a responsibility here (because you do).

Foster Diversity: Ensure diverse teams with varying perspectives participate in building and testing AI systems. Proactively seek input from various stakeholders and communities that may be impacted using AI, incorporating feedback into evaluation processes and procedures.

Drive Responsibility: Champion solid guidelines and governance structures within the organization. Encourage open dialogue about potential biases and unintended consequences. Understand that no AI solution is perfect.

Conclusion

Bias in modern AI is an increasingly complex beast, deeply tied to how these systems are designed, trained, and deployed. Challenges arise not only from bias within historical training data, but also from ongoing interactions, algorithmic design, and even the methods used to help mitigate it.

For organizations seeking to leverage AI responsibly and effectively, treating bias mitigation as a continuous process of management, monitoring, and adaptation (rather than a simple fix) is what makes or breaks the successful adoption and value chain. This requires us to adopt systemic thinking, incorporating many diverse perspectives within the AI lifecycle, and agree to a proactive commitment to fairness.